- Structuralism (french) and after

- French structuralism and after

De Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, Barthes, Lacan, Foucault

Hugh J.Silverman

FERDINAND DE SAUSSURE

The history of structuralism cannot be thought without Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–

1913). The Swiss linguist lecturing in Geneva in the early twentieth century set the scene

for what in the two and a half decades following the Second World War came to be

known as structuralism. The figures who dominated the development of the movement in

the 1940s and 1950s were Claude Lévi-Strauss (b. 1908), Jacques Lacan (1901–82), and

Roland Barthes (1915–80). By the 1960s Michel Foucault’s (1926–84) reformulations

and even rejections of structuralism indicated the new directions for what became

poststructuralism.

Curiously, the parallel development of existential phenomenology in France ran a

different course. With the possible exception of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s (1908–61)

interests in the structuralist alternative, structuralism had little or no effect upon the

development of phenomenology as a philosophical movement. With poststructuralism,

however, the confluence of these two different philosophical methods marked the

appearance of an entirely new mode of thinking—one which is exemplified in Foucault’s

archaeology of knowledge on the one hand and Jacques Derrida’s (b. 1930)

deconstruction on the other. For the purposes of the present chapter however, I shall take

Foucault as exemplary of this new development.1

Structuralism—and especially French structuralism—cannot be understood apart from

de Saussure’s semiology. According to de Saussure—as articulated clearly in the

posthumously published Course in General Linguistics (1916), a compilation of several

years of the Swiss linguist’s Geneva lectures [11.1]—semiology is ‘the general science of

signs’. De Saussure proposed a new understanding of the notion of ‘sign’. He argued that

the sign is not just a word but rather that a sign is both a word and concept. He named

these two components of the sign the ‘signifier’ [signifiant] and the ‘signified’ [signifié].

The signifier is the word, that which does the signifying. The signified is the concept, that

which is signified. Together these two components constitute a binary pair called the

sign. The standard example which de Saussure offers for this binary relation is the word

tree and the concept ‘tree’.

A sign, however, is not yet a sign until it is distinguished from other signs in the same

system, or language [langue]. A sign cannot be on its own—apart from all other elements

of the language. Indeed, de Saussure defines a sign as determined by its difference from

all other signs in the sign system. Hence the sign tree is the sign tree by its difference

from other signs such as house, bird and sky. Now the sign tree is also different from the

sign arbre or the sign Baum, arbor or arbol. Each of these other signs is part of a

different sign system: arbre, the French language, Baum, the German language, arbol,

the Spanish language. Because they are not part of the same sign system, they are signs

only in their respective sign systems.

De Saussure also remarks that the relation between a signifier and a signified is

entirely ‘arbitrary’. That the concept or signified ‘tree’ is designated by the word tree in

English is simply arbitrary. It could have been called arbre, Baum or arbol—and indeed

in different languages it does acquire such signifiers. Only in the limited instances of

onomatopoeia in which a signifier corresponds in a motivated way to a particular

signified is the arbitrary nature compromised. Hence bow-wow for a dog’s bark, or

smooth, for something soft and gentle, or Being-in-the-world for the extensiveness of our

existence are connected in a more related way than most words with their corresponding

concepts.

A sign—a signifier [un signifiant] and a signified [un signifié]—is one among many

signs in a language [langue]. A langue can be English, French, German, Japanese,

Russian, etc. In the account of a langue nothing need be spoken as such. Hence, de

Saussure offers a correlative concept called the speaking of the language or parole. While

langue is constituted by elements that make up a particular language, parole is the

speaking of that language in a determinate context and at a determinate time. Hence when

I say: ‘Tall evergreen trees inspire a sense of grandeur’, I am saying [parole] these words

(with their corresponding concepts) in English. Were I to say: ‘Ces grands arbres verts

sont magnifiques’, I am saying something else in French but I am enacting the French

language in a particular context and at a specific time—the saying is parole.

Another binary pair (or binary opposition), as Saussure sometimes calls them, is the

relation between ‘syntagm’ and ‘system’ (or ‘paradigm’). The sentence ‘Tall evergreen

trees inspire a sense of grandeur’ is a sequence of signs; one follows the other. As a

sequence, the signs follow a syntagmatic line. Each sign is contiguous with the next, and

there is a meaning produced by the sequence. By contrast, were one to substitute alternate

signs such as ‘short’, ‘broad’, or ‘imposing’ for ‘tall’, for instance, the sentence would

read: ‘Short (or broad, or imposing) evergreen trees inspire a sense of grandeur.’ The new

sentence with the substituted term still makes sense, but the sense is of course different—

and even in the first two instances a bit curious. What does not quite fit with ‘tall’,

‘short’, and ‘broad’ is ‘imposing’. The first three are all signs of size. ‘Imposing’ is of

another order, yet it is also substitutable for ‘tall’. All of these substitutable terms are part

of the same system (or paradigm) if broadly interpreted. If more narrowly interpreted, the

system could be restricted to signs of size and not just signs that are substitutable. Each of

the elements of the sentence could be examined in terms of substitutable signs, and each

would be part of a different system.

A fourth binary opposition is that between diachrony and synchrony. A diachronic

study of the Greek sign of excellence aretē would follow it through its Latin version in

virtus, its Italian reformulation as virtú, its French usage as vertu, a term which is also

repeated in English (virtue). To study the same work over time, chronologically, allows

for the consideration of a development over time, historically, as it were. However, such

a study isolates what is studied from its context and framework. It takes the element and

reviews the whole development independently of related concerns. A synchronic study,

by contrast, is ultimately concerned with the set of relations among a whole complex of

signs and elements that arise at the same time and in the same context. The sign aretē is

studied in relation to other signs at the time: paideia (education and the ideals of the

culture), sophrosyne (moderation or temperance), and so forth. In this respect a given

notion is understood in a broad context—in this case, a cultural context. Once the

synchronic study has been accomplished for a given time-slice, it will be possible to

compare that time-slice with other periods of time—in order to show similarities and/or

differences across a number of different time-slices.

As a linguist, de Saussure was ultimately concerned with language. Indeed, the whole

project of structuralism is framed according to a linguistic model. This model presumes

that what is outside language is not relevant to the linguist’s task. Hence the earliest

forms of structuralism were restricted to the formulations of a semiology based on

language study. Roland Barthes, by contrast, in his Elements of Semiology (1964 [11.7]),

remarks that while de Saussure believed that linguistics is a part of semiology—that there

are domains of semiology that are not relevant for the linguist—in his view, semiology is

a part of linguistics. Barthes’s formulation presumes that all sign systems are already

language systems of one sort or another—I shall return to Barthes later.

CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS

What is significant here is that when Lévi-Strauss in the late 1940s began to apply

structuralist principles to anthropological concerns, he was already extending the

linguistic model far beyond language study. This meant that although Lévi-Strauss as an

anthropologist was concerned with structures of thought, he had already made the shift

that Barthes articulates: ethnology is already a language which can be studied by the

structuralist.

Although de Saussure was lecturing on structural linguistics in the first decades of the

century, it took until the 1930s for his work to become noticed and accessible to a

broader context. This was the fate of his Course in General Linguistics. When Lévi-

Strauss travelled to the United States during the Second World War, it was out of

political and personal necessity as he narrates in considerable detail in Tristes tropiques

[11.3]. When he arrived in New York, he began teaching at the University in Exile

(which has subsequently come to be called The New School for Social Research). During

that time, he met and conferred often with Roman Jakobson (1896–1982) (whose own

itinerary had taken him from Russia to Prague to Paris to New York). Jacobson was a

linguist whose development of Russian formalism was an important contribution to the

concept of structure. Indeed both Lévi-Strauss and Jakobson worked together on a

groundbreaking reading of a Baudelaire poem, ‘Les Chats’. The idea was to offer a

structural study of the poem. Their reading was careful and meticulous. They were

interested in how the poem exhibits structural, stylistic and syntactic features in order to

constitute the work as a whole. Jakobson’s further interest in metaphor and metonymy

was worked out in his Fundamentals of Language [11.50] in terms of two types of

aphasia: metaphor as replacement by substitution, metonymy as replacement by

contiguity.2

After the war, Lévi-Strauss served as cultural adviser to the French ambassador to the

United States (1946–7). Then he returned to France where he took up his position at the

Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (the ‘Pratique’ has subsequently

been dropped) and resumed his research in structural anthropology. In 1949, he produced

his major contribution, The Elementary Structures of Kinship [11.2]. Here the concept of

kinship was developed in connection with Lévi-Strauss’s understanding of structuralism

and his collation of many different ethnographic accounts of kinship throughout the

world. His view was that despite many significant differences in kinship practice in

different cultures, common structures are repeated underneath these multiple instances of

kinship practices. These structures have a basic form according to a determinate set of

relations. The actual character of the relation might change from one context to another,

but what does not change is the relation itself. Each relation is part of a whole structure of

relations, where no element is strictly independent of any of the others. Thus a one-to-one

correspondence of one part of a structure with one part of another cannot be made. The

whole structure must be compared with another whole structure in order to provide an

appropriate analysis. For instance, Lévi-Strauss is particularly interested in the

‘avunculate’ or uncle-relation. He finds from his extensive research of many different

cultures, societies and social groups that the role of the uncle is critical. Hence there is the

mother-father relation, the mother-father and son relations, the son-maternal uncle

relation, and the mother-brother relation.

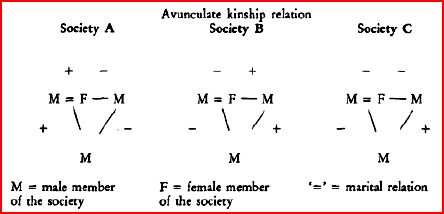

Understood independently, each of these relations has a particular content: positive and

socially supported in one case, negative and outcast in another. Lévi-Strauss determined

that by assigning a positive or negative value to each of these relations in a particular

context, he could determine the nature of the whole structure. For three hypothetical

societies, it might look like Fig. 11.1.

In each of these societies, the mother and father, the mother’s brother and the brother’s

sister’s son constitute the key kinship relations. While the structure recurs, the nature of

the relations change from one society to the next. The repetition of the same structure is

matched with the differences in the nature of the relations among the social roles in each

society.

This concept of structure indicates a latent set of relations that underlie the actual,

particular and real relations of specific individuals in a determinate context. Lévi-Strauss

broadens his reading of kinship relations to the account of totems and taboos in different

societies as well as to the detailed study of myths. These further explorations of the

application of structural method resurface in a variety of essays written between 1944 and

1957 and are collected together in the first volume of Structural Anthropology (1958

[11.4]). The appearance of Structural Anthropology marked a significant phase in the

development of structuralism. Elementary Structures (1949, [11.2]) was highly detailed

and technical. The new book solidified the role of structuralism in France. It indicated

that there was now an alternative research programme that would ultimately match that of

existentialism and the existential phenomenology that had reigned unopposed since the

early 1940s. While it would take another decade for structuralism to establish its foothold

firmly, Lévi-Strauss’s new book was an important link between the growing interest in de

Saussure’s semiology and the full-fledged structural studies that Barthes, Lacan and

Foucault would carry on into the 1960s. This is not to say that Lévi-Strauss has not been

a continuing and dominant force in the development of structuralism even today. At the

beginning of the 1970s, when I attended his lectures at the Collège de France where he

occupies the Chair of Social Anthropology, he was still defending his position against the

comments and criticisms of the British anthropologist Rodney Needham. And many

books have followed the appearance of Structural Anthropology. His four-volume study

of world mythologies, his second volume of Structural Anthropology, his

autobiographical Tristes tropiques, his many essays on masks and race all add up to a

major contribution to late twentieth-century French thought.

Louis Marin (1931–92) used to comment that when he was a young man in the early

1950s, he and his wife Françoise were invited to the apartment of M. and Mme Maurice

Merleau-Ponty for what was then described as a ‘dîner intime’. When he and his wife

arrived, he discovered that it was indeed a small diner party: M. and Mme Merleau-

Ponty, M. and Mme Lévi-Strauss, and M. and Mme Lacan. That these three were all

friends indicates a certain collaboration and dialogue that was highly charged in the early

period in which structuralism was gaining hold. Although Merleau-Ponty is known for

his groundbreaking work as a phenomenologist of perception (1945), only a year later he

was lecturing on de Saussure at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. Merleau-Ponty’s

turn to semiology as a topic of interest began to blend with his commitment to the

achievements of Gestalt psychology, but even more with those of phenomenology which

he saw as superior even to the Gestalt theories of Köhler and Koffka, Gelb and Goldstein.

Yet with his growing interest in language, Merleau-Ponty found real value in the

Saussurian theory of the sign.3 His courses on ‘Language and Communication’ (1946–7)

stressed his new commitment to language—a topic which he had only broached in

Phenomenology of Perception (1945), notably in the chapter on ‘The Body as Speech and

Expression’. Hence concurrently with Lévi-Strauss’s return to France and his intense

work on kinship relations, his friend Merleau-Ponty, who was by then Professor of Child

Psychology and Pedagogy at the Institut de Psychologie in Paris, was also developing a

serious interest in the implications of Saussure’s structural linguistics.

When Merleau-Ponty set himself the task of writing a kind of literary theory which

was to have seen the light of day in the early 1950s, he was setting the stage for an

important debate that would take shape throughout the 1950s and 1960s—even long after

his death in 1961. What became The Prose of the World (published posthumously in

1969) [11.64]) , was to have been completed in 1952. However, Merleau-Ponty was

elected to the Collège de France that year and his research took him in other directions,

most notably in his critique of ‘dialectic’ and towards his theory of visibility in The

Visible and the Invisible (1964). There were two companion pieces that have been

included in Signs (1960 [11.62]) which addressed the question of language: ‘The

Phenomenology of Language’ and ‘Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence’. These

two essays, written in 1951–2, indicate the convergence between phenomenology and

structuralism as it was under development in the French context. While Sartre continued

to reject structuralism vigorously,4 Merleau-Ponty continued to be intrigued. While Sartre

published his own theory of literature in Qu’est-ce que la littérature? in 1947, he oriented

this theory toward the act of communicating the freedom of a writer to the freedom of a

reader. Writing, for Sartre, was both an act of commitment and an expression of freedom.

Merleau-Ponty’s response came in 1952 with The Prose of the World: there are many

aspects of language and expression that are simply not direct, that do not give an

algorithmic reading of experience—literature and painting are prime examples. Here

there is language but indirectly expressed—even silence for Merleau-Ponty speaks.

ROLAND BARTHES

Like Merleau-Ponty, the second major figure of French structuralism, Roland Barthes,

was also preparing in 1952 a response to Sartre’s literary theory: Writing Degree Zero

[11.5] was of mould-breaking merit. It offered an entirely different way of understanding

the role and status of writing. Writing was no longer an act of communication, but rather

an articulation that links up both style and language. The writer’s style (whether

romantic, or surrealist or existentialist) is matched with the writer’s langue or language.

This language is not simply idiosyncratic. For Barthes, language partakes of a social

context and experience. Language and style at the intersection of the two marks the locus

of writing (écriture). Hence revolutionary writing or bourgeois writing or romantic

writing occur in terms of a particular language and a determinate style. And such

revolutionary writing can be found equally in the times of Thomas Jefferson, Robespierre

and Brecht. Though the times are radically different, even the language and style are

different, the writing can be called ‘the same’. Although Barthes found that different texts

could be characterized in terms of these repeatable forms of writing, he was also

fascinated with the new writing of Alain Robbe-Grillet. Barthes is credited with having

‘discovered’ Robbe-Grillet, whose style of writing is officially a radical break with the

nineteenth-century novel, but whose writing itself marks the beginning of an

impassionate language where the subject is decentred and the discursive proliferations are

structurally identifiable. Le Voyeur and La Jalousie are excellent examples of a language

stripped of emotion—or at least emotion as described by the typical nineteenth-century

omniscient author. There is still emotion, but it is described through the surfaces and the

ways in which surfaces are affected.

With the 1964 publication of Elements of Semiology [11.7], Barthes at last linked up

his critical practice with the theoretical writings of de Saussure. In this short piece, which

was originally published in Communications, the official journal of the Ecole Pratique

des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Barthes outlines the theory of the sign: the

signifier/signified relation, the langue/parole link, the connection between diachrony and

synchrony, and the opposition between denotation and connotation. But the critical year

was 1966, which saw the publication of his own Criticism and Truth [11.8], Lacan’s

Ecrits, [11.15] and Foucault’s The Order of Things [11.17]. Hence over a decade after

Barthes produced Writing Degree Zero, structuralism finally came of age. Elements of

Semiology set the stage for that crowning moment. In his seminar at the Ecole Pratique

des Hautes Etudes which I attended for the whole year in 1971–2, Barthes focused on

what he called ‘The Last Decade of Semiology’. He considered 1966 as the watershed

year. In the following year, Jean-Luc Godard produced his revolutionary film La

Chinoise (which prefigured the student-worker revolts of 1968) and Derrida published

Speech and Phenomena [11.30], Of Grammatology [11.29], and Writing and Difference

[11.31]. Hence by 1967, a whole new phase had begun—for lack of a more precise term

it was called poststructuralism. Of course, there were still many who were committed to

structuralism for another decade and many of the so-called poststructuralist theories

continued to build upon the languages and lessons of structuralism.

Once the scene was set and the terminology clarified in The Elements of Semiology

[11.7], Barthes himself began to develop his own position further. He rejected those

critical theories that gave special place to the author and authorial presence. And in his

famous essay ‘From Work to Text’ (1971 [11.10]), he outlined very clearly the

distinction between the traditional notion of the ‘work’ and his notion of the ‘text’. The

‘work’ (oeuvre, opera, Werk) results from an act of filiation: an author produces or

creates a work which is then a ‘fragment of substance, occupying a part of the space of

books (in a library for example)’.5 The author requires authority over the meaning of the

work. And the critic seeks to understand the author’s meaning. This hermeneutic concern

pervades work-centred studies. And it was also a dominant feature of the Sartrian theory

as well. Barthes proposes to place the emphasis on the text, which he describes as a

‘methodological field’. He elaborates: ‘The Text can be approached, experienced, in

reaction to the sign. The work closes on a signified’ (p. 158). This means that the text can

be read in terms of the sign system which participates in it, while the work focuses on

what is meant by it. The plurality of the text permits a full and elaborate network of

intertextuality which is closed off by the work. ‘The Text’, he says, ‘is bound to

jouissance, that is to a pleasure without separation’ (p. 164).

Two years later, Barthes published The Pleasure of the Text (1973, [11.11]). For

Barthes, the Text is not an object of desire or even a result of a creative act. Rather the

Text is a site—a locus for a reading, a place in which jouissance occurs. Something

happens in the critical reading of a Text. The Text’s network of signifying dynamic is

brought out. In the Introduction to S/Z (1970), Barthes had already shown how the

distinction between the ‘readerly’ (lisible) and ‘writerly’ (scriptible) text marks the

difference between a text which is simply read through for the pleasure of it and the text

which is read as a methodological field—one in which the codes and sign systems are

elaborated in detail and available for careful decoding. The ‘writerly text is not a thing,’

Barthes writes, ‘we would have a hard time finding it in a bookstore.’6 The ‘writerly is

the novelistic without the novel, poetry without the poem, the essay without the

dissertation, writing without style, pro-duction without product, structuration without

structure’ (p. 5). The writerly occupies only a methodological and theoretical space, it is

not a product like the readerly text.

In this frame, Barthes outlined five different codes which constitute what he calls ‘the

plural text’, and the plural text is the writerly text critically disclosed. The five codes

include: the semic code (the elaboration of the signifier), the hermeneutic code

(disclosure of the enigma), the symbolic code (one element stands for another), the

actantial code (the action code), and the reference code (the cultural indicators marked in

the text). These codes are only possible codes for the reading of a text. Although Barthes

does not dwell upon the alternatives, it is only plausible that alternative sets of codes

function as well as those Barthes invokes.

Barthes was at his most daring when he took up an age-old topic, namely

autobiography, but in a radically new way. Roland Barthes (1975, [11.12]) by Roland

Barthes is certainly a break with the traditional diachronic mode of writing one’s own

life. He organizes his life not according to the succession of years, but according to the

alphabetical arrangement of topics, themes and oppositions that played an important role

in his life. And as to the typical chronology, that can be found in two pages at the back of

the essay. Barthes should not have died so early. He was run over by a milk truck outside

the Collège de France where he had been elected to the Chair of Semiology in 1977. He

was only sixty-five when he died in 1980.

JACQUES LACAN

Jacques Lacan, by contrast, born in 1901 only one year after Hans-Georg Gadamer, lived

to a ripe old age of eighty-one. There is a wonderful cartoon which Barthes includes in

his Roland Barthes of Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, Barthes, Foucault and Michel Leiris all sitting

together in Tahitian skirts. Although reflecting different ages, they all came together

around the structuralist enterprise. Lacan provided the basis for a structural

psychoanalysis. His early 1936 study of the mirror stage was first presented in Marienbad

(later made famous by Robbe-Grillet in the film Last Year at Marienbad). Lacan’s theory

is rather simple: the child at first does not detect any difference between it and its mother.

The sensory world around it is all integrated. It begins to notice a difference between it

and the mother. This becomes clear when it looks into the mirror and sees no longer just

motion or another person, but recognizes an identity between what it sees and itself. It

waves an arm and the image waves its arm, etc. It notices then that the mirror image is

itself. But then the father intercedes: the nom du père/ non du père/non-dupe erre are all

forms of interdiction. The father with his name and his prohibition—after all, he is

somewhat jealous of the close relationship that his child has with his wife—attempts to

break the harmony, introduces a negation, his paternal law, his ‘No’. The father is no

fool. He knows what he wants and he knows what he does not want. By interceding

between the child and the mother, he imposes his authority, his will, his name. Now the

child cannot but recognize difference. The Verneinung is effective. The father imposes

his will and the child learns to affirm its own identity. Thus the mirror stage is the critical

moment at which the child takes on an identity of its own.

The inclusion of the revised version of the ‘Mirror Stage’ in Ecrits (1966 [11.15])

correlates with a number of other essays of major importance. In 1966 there was a

conference held at Johns Hopkins University subsequently entitled The Structuralist

Controversy. While Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato edited the volume, the

leadership of René Girard was crucial. At Stanford, for instance, in the late 1960s one

heard of the Johns Hopkins experiment and those professors of literature committed to an

earlier model of literary study were deeply opposed to the Johns Hopkins scene.

Curiously, René Girard is now Professor of Humanities at that very same Stanford

University after trying out the State University of New York at Buffalo for a brief period.

Lacan was one of the speakers at the 1966 Hopkins conference. Also presenting papers

were Jean Hyppolite and Jacques Derrida. It was an important moment. And Lacan’s

essay was no less important. His paper was entitled ‘The Insistence of the Letter in the

Unconscious’, an essay which also appears in Ecrits. The question is, how does the chain

of signifiers mark off and bar the range of the signified? The signified especially in the

metonymic line is barred from access by the signifier. This exclusion of the signified

leads to a veering off of the signifier from one sign to the next. The signified however

remains unaccessible. The line between the signifier and the signified is strong and

resistant. In such cases in which the signifier has no access to the signified, it must act in

terms of that repression.

In the case of metaphor, there is an overdetermination of signifieds for a particular

signifier. In such a case, the bar is weak and a multiplicity of meanings intrude.

Throughout Lacan’s account, ‘the unconscious is structured like a language’. Where there

is resistance in language, there would be resistance in the unconscious. But for Lacan

whatever there is of an unconscious is read in terms of the play of signifiers. Repression

results when the letter is unable to insist in the signified. Meaning is kept at bay. A

stream of words and utterances follows but the relation to the signified is repressed. With

Lacan, as later with Derrida, the self is decentred, the subject is dispersed throughout

language. The language of the self is the language of the chain of signifiers. The subject

per se remains absent.

MICHEL FOUCAULT

The theme of the absent subject is especially notable in the philosophy of Michel

Foucault, who met an untimely AIDS-related death at the early age of fifty-eight. In his

magnum opus, The Order of Things (Les Mots et les choses) [11.17] also published in

1966—the theme of the absent subject pervades not only his reading of Velázquez but

also his account of the contemporary human sciences. For contemporary

(poststructuralist, or what would now be called ‘postmodern’) thought, there is no centred

origin, no unique place of focus, no present subject as there once was for the modern age.

Foucault’s reading of origins is marked off by his reading of discursive practices. As

he demonstrates in The Order of Things, history does not begin at a certain moment and

then continue—in linear fashion—from then on. Rather, moments of dominance of

certain discursive practices prevail for a time and are then succeeded by a new set of

discursive practices. Where a discursive practice ends, a new one is about to begin.

Origin then will occur where a new discursive practice starts to take place. But where and

when do such new practices begin to take place? They clearly do not occur at a

determined moment in time such as a date or year. Certain discursive practices pertinent

to a particular epistemological space, as Foucault calls it, continue into a new

epistemological space, while others die out.

But what is a discursive practice? For Foucault, a discursive practice is a whole set of

documents produced within a broadly general period of time in which common themes or

ideas occur across that period in a wide variety of disciplines and areas of human

knowledge production. For instance, in the nineteenth century the relations between

biology, economics and philology would seem to be entirely unrelated. However

Foucault has shown that they all consolidate in terms of a relatively singular conceptual

unity, or what Foucault calls an epistemé. For the broad space of the nineteenth century,

Foucault identifies the theme in question with what he calls an ‘anthropology’, that is, the

theory of ‘man’ as defined by the ‘empirico-transcendental doublet’,7 the particular

Kantian idea that empirical (objective) considerations must always be understood in

connection with a transcendental (subjective) set of conditions that permeates the

discursive practices of the nineteenth century. The theme of subjectivity in relation to

objectivity pervades the nineteenth-century understanding of life, labour and language.

Thus the discursive practices of the nineteenth century repeat themselves in a variety of

contexts—all explicitly unrelated to each other. These differences then form an epistemé.

The epistemé of the nineteenth century succeeds the epistemé of the ‘classical age’.

This prior epistemological space is marked by another set of discursive practices. These

include the classification of species, the analysis of wealth and natural grammar. What

one would take to be entirely unrelated concerns are here brought into relation to one

another in that they each exhibit features of the ‘classical age’ epistemé, namely

‘representation’. As Foucault reads the general period of the seventeenth century and first

half of the eighteenth century, the idea of ‘representation’—the projection or postulate of

ideas before the mind—formed the frame for a distinctly ‘classical’ way of thinking. The

relation between this classical epistemé and the nineteenth-century epistemé is much less

significant than the relation between the various practices at each of these respective

time-slices.

The origin of the epistemé is not the beginning of the epistemé. A particular epistemé is

marked by a certain dominance. The place where the epistemé dominates is the place of

its origin. The place of dominance for the empirico-transcendental doublet is the place of

origin within that epistemological framework. Similarly the place of dominance of

representation in the classical age is the place of origin within that epistemological

framework. However, where is this place of origin in each case? Dispersed throughout

the epistemological space, the place of origin occurs wherever there is a discursive

practice that exhibits it. Hence the origin is in many places: reappearing in many

locations throughout the epistemological space itself. In the nineteenth century, one can

find the empirico-transcendental doublet not only in Hegel and Hölderlin but also in

biologists such as Cuvier (whose ‘fixism’ is set off against the backdrop of human

historicity), economists such as Ricardo (for whom history is a vast compensating

mechanism) and philologists such as Schlegel (with his 1808 essay on the language and

philosophy of the Indians), and philologists such as Grimm (most notably in the 1818

Deutsche Grammatik) and Bopp (whose 1816 study of the Sanskrit conjugation system

became an object of study).

Each of these places constitutes itself as an origin, as a locus in which the concept of

‘man’ as a subject-object is brought into discourse production itself. No longer does

language, for instance, operate between words and things resulting in an operation of

representation. And in the nineteenth century, words are objects themselves, objects for

scrutiny and study by a scientific practice that hopes to judge them and their

interrelationships. Origin, then, for Foucault is not a source from which all historical

events follow. Origin is not the beginning from which history begins to unfold. Origin is

not the inception from which development ensues. Origin does not establish the moment

before which nothing else will have occurred. Rather origin springs up in many places

within a broad, general, historical time-frame. Origins occur in various discourses,

scarring them with marks of a common practice that is unaware of its own commonality.

Foucault’s enterprise disperses origin throughout a kind of methodological field (as

Barthes would have called it). And his appeal to the English reader to ignore those ‘tiny

little minds that persist in calling him a structuralist’, indicates that he is already beyond

the mere repetition of structuralist methods. Although his own archaeology of knowledge

could be characterized as largely synchronic, it also relies upon the assessment of periods

or time-slices in order to compare one time-slice with another. What Foucault rejects is

the necessity of a concept of continuity in favour of discontinuity. Structuralists were

already concerned with a discourse of the past. Nietzsche and Mallarmé are invoked as

threshold figures marking the break with the older empirico-transcendental doublet of the

modern age. They mark the beginning of a new mode of thought in which dissemination,

dispersal, metonymy and decentring of the subject are the dominant frames of knowledge

production.

Where Sartre had announced in his 1936 Transcendence of the Ego that the self or ego

could not be located in consciousness but is at best an object of consciousness, Foucault

in 1966 places that claim in a historical context. He situates the end of the age of

modernism with the end of the centred subject, the dominant self, the focal ‘I’. Like

Nietzsche’s madman who ran through the streets proclaiming the ‘death of god’, Sartre

had already proclaimed ‘the end of man’, but in a sense that would not be fully

understood for another thirty years. The linguistic turn in continental philosophy took on

a different shape from that in the analytic tradition. It did not fully take place until the

Saussurian epistemology became the principle according to which language, culture and

knowledge production would be understood. The structural analysis of kinship, totems

and myths in Lévi-Strauss, the speaking subject’s chain of signifiers in Lacan, the

semiological analysis of text and culture in Barthes were themselves placed in context by

Foucault. In this respect, Foucault is indeed already after structuralism, for he is able to

situate it as a movement in a period of time. The subsequent development of Foucault’s

own genealogy, Derrida’s deconstruction, Deleuze’s nomadologies, Kristeva’s

semanalysis and Lyotard’s postmodernist sublimities are all themes for another story in

the history of continental thought. Suffice it to say that structuralism played a critical role

in offering an alternative to existential phenomenology and at the same time a

complement to it. What comes after structuralism (and after the age of the modern

subject) is identified by those such as Foucault who were themselves marked by both

phenomenology and structuralism and who were in a position to succeed them as well.

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

de Saussure

11.1 Course in General Linguistics (1916), trans. W.Baskin, New York: McGraw-Hill,

1959.

Lévi-Strauss

11.2 The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949), trans. from the revised edition by

J.H.Bell and J.von Sturmer, and ed. R.Needham, Boston: Beacon, 1969.

11.3 Tristes tropiques (1955), trans. J. and D.Weightman. New York: Atheneum, 1974.

1 Derrida’s deconstruction is left aside here for the simple reason that it is taken up in another

contribution to this same volume. A portion of the discussion of Foucault is taken from

H.J.Silverman, Textualities: Between Hermeneutics and Deconstruction (New York and

London: Routledge, 1993).

2 The role of metaphor and metonymy have been subsequently linked with what Freud calls

‘condensation’ and ‘displacement’ in dream interpretation. Hence metaphor as substitution

and condensation implies the replacement of a father by a big bear (for instance) in a young

boy’s dream, while metonymy as contiguity and displacement results in a dream about a

neighbour’s garden hose (for instance) instead of her passion for him. In structural political

theory, developed most notably by Louis Althusser—in an essay called ‘Freud and Lacan’

from Lenin and Philosophy [11.23] metaphor is associated with overdetermination in a

reading of a political text or context, while metonymy is represented as underdetermination.

In making this point, Althusser is building on the account of metaphor and metonymy offered

by Lacan in his famous essay ‘The Insistence of the Letter in the Unconscious’ (included in

Ecrits [11.15]) and H.J.Silverman [11.72], especially the chapter on ‘Merleau-Ponty on

Language and Communication (1946–47)’.

3 See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Consciousness and the Acquisition of Language [11.65].

4 See H.J.Silverman [11.72], esp. chapters on ‘Sartre and the Structuralists’ and ‘Sartre versus

Structuralism’.

5 R.Barthes, ‘From Work to Text’ [11.10], 155–64.

6 R.Barthes, S/Z [11.9], 5.

7 See Silverman [11.72], esp. chapter 18 on ‘Foucault and the Anthropological Sleep’.

11.4 Structural Anthropology (1958), trans. C.Jacobson and B.G.Schoepf, New York:

Basic Books, 1963.

Barthes

11.5 Writing Degree Zero (1953), trans. A.Lavers and C.Smith, New York: Hill & Wang,

1968.

11.6 Michelet, Paris: Seuil, 1954.

11.7 Elements of Semiology (1964), trans. A Lavers and C.Smith, New York: Hill &

Wang, 1968.

11.8 Criticism and Truth (1966), trans. K.P.Kenneman, Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1987.

11.9 S/Z (1970), trans. R.Miller, New York: Hill & Wang, 1974.

11.10 ‘From Work to Text’, in [11.13], 155–64.

11.11 The Pleasure of the Text (1973), trans. R.Miller, New York: Hill & Wang, 1975.

11.12 Roland Barthes (1975), trans. R.Howard, New York: Hill & Wang, 1977.

11.13 Image-Music-Text, trans. S.Heath, New York: Hill & Wang, 1977.

11.14 Recherche de Proust, Paris: Seuil, 1980.

Lacan

11.15 Ecrits (1966), trans. A.Sheridan, New York: Norton, 1977.

11.16 ‘Seminar on “The Purloined Letter”’, trans. J.Mehlman, French Freud: Structural

Studies in Psychoanalysis, Yale French Studies 48 (1972): 38–72.

Foucault

11.17 The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences (1966), trans. anon.,

New York: Vintage, 1970.

11.18 The Archeology of Knowledge (1969), trans. A.Smith, New York: Pantheon, 1972.

11.19 ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice (1971),

trans. D.Bouchard and S.Simon, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 139–64.

11.20 Discipline and Punish (1975), trans. A.Sheridan, New York: Vintage, 1979.

Other works and criticism

11.21 Allison, D.B. (ed.) The New Nietzsche, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1977, 1985.

11.22 Allison, D.B. ‘Destruction/Deconstruction in the Text of Nietzsche’, Boundary 2,

8:1 (fall 1979):197–222.

11.23 Althusser, L. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. B.Brewster, New

York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

11.24 Blanchot, M. ‘Discours Philosophique’ in L’Arc: Merleau-Ponty, 46 (1971): 1–4.

11.25 Blanchot, M. Death Sentence, trans. L.Davis, New York: Station Hill, 1978.

11.26 Culler, J. Structuralist Poetics, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975.

11.27 Culler, J. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism After Structuralism, Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 1982.

11.28 Derrida, J. Edmund Husserl’s Origin of Geometry: An Introduction (1962), trans.

J.Leavey, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

11.29 Derrida, J. Of Grammatology (1967), trans. G.C.Spivak, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1975.

11.30 Derrida, J. Speech and Phenomena, and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs

(1967), trans. D.B.Allison, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1973.

11.31 Derrida, J. Writing and Difference (1967), trans. A.Bass, Chicago: University of

Chicago Press and London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

11.32 Derrida, J. Dissemination (1972), trans. B.Johnson, Chicago: University of

Chicago Press and London: Athlone Press, 1981.

11.33 Derrida, J. Margins of Philosophy (1972), trans. A.Bass, Chicago: University of

Chicago Press and Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1982.

11.34 Derrida, J. Positions (1972), trans. A.Bass, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

and London: Athlone, 1982.

11.35 Derrida, J. ‘The Deaths of Roland Barthes’ (1981), trans. P.A.Brault and

M.B.Naas, in H.J.Silverman (ed.) Philosophy and Non-Philosophy since Merleau-

Ponty (Continental Philosophy-I) , London and New York: Routledge, 1988, pp. 259–

96.

11.36 Derrida, J. ‘The Time of a Thesis: Punctuations’, in Alan Montefiore (ed.)

Philosophy in France Today, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

11.37 Derrida, J. Signéponge/Signsponge, trans. R.Rand, New York: Columbia

University Press, 1984. (Parallel French and English translation.)

11.38 Descombes, V. Modern French Philosophy, trans. L.Scott-Fox and J.M. Harding,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

11.39 Donate, E. and Macksey, R. (eds) The Structuralist Controversy, Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1972.

11.40 Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976.

11.41 Fekete, J. (ed.) The Structural Allegory: Reconstructive Encounters with the New

French Thought, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

11.42 Felman, S. (ed.) Literature and Psychoanalysis: The Question of Reading—

Otherwise, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

11.43 Gasché, R. ‘Deconstruction as Criticism’, Glyph 7 (1979):177–216.

11.44 Gasché, R. The Tain of the Mirror: Deconstruction and the Philosophy of

Reflection, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986.

11.45 Hartman, G. Beyond Formalism, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.

11.46 Hartman, G. The Fate of Reading, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

11.47 Hartman, G. Criticism in the Wilderness, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

11.48 Hartman, G. Saving the Text: Philosophy/Derrida/Literature, Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1981.

11.49 Hawkes, T. Structuralism and Semiotics, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press, 1977.

11.50 Jakobson, R. ‘Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasia’, in

Fundamentals of Language, The Hague: Mouton, 1971.

11.51 Kearney, R. Dialogues with Contemporary Continental Thinkers: The

Phenomenological Heritage, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984.

11.52 Kearney, R. Modern Movements in European Philosophy, Manchester: Manchester

University Press, 1986.

11.53 Kristeva, J. Desire in Language, trans. T.Gora, A.Jardine and L.Roudiez, New

York: Columbia University Press, 1980.

11.54 Kristeva, J. Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. M.Waller with an introduction

by L.S.Roudiez, New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

11.55 Kristeva, J. The Kristeva Reader, ed. Toril Moi, New York: Columbia University

Press, 1986.

11.56 Kristeva, J. Black Sun, New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

11.57 Lacoue-Labarthe, P. ‘Fable (Literature and Philosophy)’, trans. H.J.Silverman,

Research in phenomenology, 15 (1985):43–60.

11.58 Lyotard, J.-F. The Postmodern Condition, trans. G.Bennington, Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

11.59 Marin, L. Utopics: The Semiological Play of Textual Spaces, trans. R. Vollrath,

Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press, 1990.

11.60 Merleau-Ponty, M. Sense and Non-Sense (1947), trans. H.L.Dreyfus and

P.A.Dreyfus, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964.

11.61 Merleau-Ponty, M. L’Oeil et l’esprit (1960), Paris: Gallimard, 1964.

11.62 Merleau-Ponty, M. Signs (1960), trans. R.C.McCleary, Evanston: Northwestern

University Press, 1964.

11.63 Merleau-Ponty, M. The Primacy of Perception, ed. J.M.Edie, Evanston:

Northwestern University Press, 1964.

11.64 Merleau-Ponty, M. Prose of the World (1969), trans. J.O’Neill, Evanston:

Northwestern University Press, 1973.

11.65 Merleau-Ponty, M. Consciousness and the Acquisition of Language, trans.

H.J.Silverman, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1973.

11.66 Merleau-Ponty, M. Texts and Dialogues, ed. H.J.Silverman and J.Barry, Jr.,

Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press, 1992.

11.67 Montefiori, A, (ed.) Philosophy in France Today, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1982.

11.68 Peirce, C.S. Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. J.Buchler, New York: Dover,

1940/1955.

11.69 Said, E. The World, the Text, and the Critic, London: Faber & Faber, 1984.

11.70 Silverman, H.J. ‘Phenomenology’, Social Research, 47:4 (winter 1980): 704–20.

11.71 Silverman, H.J. ‘Phenomenology: From Hermeneutics to Deconstruction’,

Research in phenomenology, 14 (1984):19–34. Reprinted, with ‘After-thoughts’, in

A.Giorgi (ed.) Phenomenology: Descriptive or Hermeneutic?, Pittsburgh: Duquesne

University Phenomenology Centre, 1987, pp. 19–34 and 85–92.

11.72 Silverman, H.J. Inscriptions: Between Phenomenology and Structuralism, London

and New York: Routledge, 1987.

11.73 Silverman, H.J. (ed.) Philosophy and Non-Philosophy since Merleau-Ponty

(Continental Philosophy—I), London and New York: Routledge 1988.

11.74 Silverman, H.J. (ed.) Derrida and Deconstruction (Continental Philosophy— II),

London and New York: Routledge, 1989.

11.75 Silverman, H.J. (ed.) Postmodernism—Philosophy and the Arts (Continental

Philosophy—III), New York and London: Routledge, 1990.

11.76 Silverman, H.J. (ed.) Gadamer and Hermeneutics (Continental Philosophy —IV),

New York and London: Routledge, 1991.

11.77 Silverman, H.J. (ed.) Writing the Politics of Difference, Albany: SUNY Press ,

1991.

11.78 Silverman, H.J. and Aylesworth, G.E. (eds) The Textual Sublime: Deconstruction

and its Differences, Albany: SUNY Press, 1989.

11.79 Sini, C. Semiotica e filosofia: Segno e linguaggio in Peirce, Heidegger e Foucault,

Bologna: Il Mulino, 1978.

11.80 Sini, C. Images of Truth, trans. M.Verdicchio, Atlantic Highlands: Humanities

Press, 1993.

11.81 Sturrock, J. (ed.) Structuralism and Since: From Lévi-Strauss to Derrida, London:

Oxford University Press, 1979.

11.82 Wurzer, W.S. ‘Heidegger and Lacan: On the Occlusion of the Subject’, in

H.J.Silverman et al. (eds) The Horizons of Continental Philosophy, Dordrecht: Nijhoff-

Kluwer, 1988, pp. 168–89.

In each of these societies, the mother and father, the mother’s brother and the brother’s

sister’s son constitute the key kinship relations. While the structure recurs, the nature of

the relations change from one society to the next. The repetition of the same structure is

matched with the differences in the nature of the relations among the social roles in each

society.

This concept of structure indicates a latent set of relations that underlie the actual,

particular and real relations of specific individuals in a determinate context. Lévi-Strauss

broadens his reading of kinship relations to the account of totems and taboos in different

societies as well as to the detailed study of myths. These further explorations of the

application of structural method resurface in a variety of essays written between 1944 and

1957 and are collected together in the first volume of Structural Anthropology (1958

[11.4]). The appearance of Structural Anthropology marked a significant phase in the

development of structuralism. Elementary Structures (1949, [11.2]) was highly detailed

and technical. The new book solidified the role of structuralism in France. It indicated

that there was now an alternative research programme that would ultimately match that of

existentialism and the existential phenomenology that had reigned unopposed since the

early 1940s. While it would take another decade for structuralism to establish its foothold

firmly, Lévi-Strauss’s new book was an important link between the growing interest in de

Saussure’s semiology and the full-fledged structural studies that Barthes, Lacan and

Foucault would carry on into the 1960s. This is not to say that Lévi-Strauss has not been

a continuing and dominant force in the development of structuralism even today. At the

beginning of the 1970s, when I attended his lectures at the Collège de France where he

occupies the Chair of Social Anthropology, he was still defending his position against the

comments and criticisms of the British anthropologist Rodney Needham. And many

books have followed the appearance of Structural Anthropology. His four-volume study

of world mythologies, his second volume of Structural Anthropology, his

autobiographical Tristes tropiques, his many essays on masks and race all add up to a

major contribution to late twentieth-century French thought.

Louis Marin (1931–92) used to comment that when he was a young man in the early

1950s, he and his wife Françoise were invited to the apartment of M. and Mme Maurice

Merleau-Ponty for what was then described as a ‘dîner intime’. When he and his wife

arrived, he discovered that it was indeed a small diner party: M. and Mme Merleau-

Ponty, M. and Mme Lévi-Strauss, and M. and Mme Lacan. That these three were all

friends indicates a certain collaboration and dialogue that was highly charged in the early

period in which structuralism was gaining hold. Although Merleau-Ponty is known for

his groundbreaking work as a phenomenologist of perception (1945), only a year later he

was lecturing on de Saussure at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. Merleau-Ponty’s

turn to semiology as a topic of interest began to blend with his commitment to the

achievements of Gestalt psychology, but even more with those of phenomenology which

he saw as superior even to the Gestalt theories of Köhler and Koffka, Gelb and Goldstein.

Yet with his growing interest in language, Merleau-Ponty found real value in the

Saussurian theory of the sign.3 His courses on ‘Language and Communication’ (1946–7)

stressed his new commitment to language—a topic which he had only broached in

Phenomenology of Perception (1945), notably in the chapter on ‘The Body as Speech and

Expression’. Hence concurrently with Lévi-Strauss’s return to France and his intense

work on kinship relations, his friend Merleau-Ponty, who was by then Professor of Child

Psychology and Pedagogy at the Institut de Psychologie in Paris, was also developing a

serious interest in the implications of Saussure’s structural linguistics.

When Merleau-Ponty set himself the task of writing a kind of literary theory which

was to have seen the light of day in the early 1950s, he was setting the stage for an

important debate that would take shape throughout the 1950s and 1960s—even long after

his death in 1961. What became The Prose of the World (published posthumously in

1969) [11.64]) , was to have been completed in 1952. However, Merleau-Ponty was

elected to the Collège de France that year and his research took him in other directions,

most notably in his critique of ‘dialectic’ and towards his theory of visibility in The

Visible and the Invisible (1964). There were two companion pieces that have been

included in Signs (1960 [11.62]) which addressed the question of language: ‘The

Phenomenology of Language’ and ‘Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence’. These

two essays, written in 1951–2, indicate the convergence between phenomenology and

structuralism as it was under development in the French context. While Sartre continued

to reject structuralism vigorously,4 Merleau-Ponty continued to be intrigued. While Sartre

published his own theory of literature in Qu’est-ce que la littérature? in 1947, he oriented

this theory toward the act of communicating the freedom of a writer to the freedom of a

reader. Writing, for Sartre, was both an act of commitment and an expression of freedom.

Merleau-Ponty’s response came in 1952 with The Prose of the World: there are many

aspects of language and expression that are simply not direct, that do not give an

algorithmic reading of experience—literature and painting are prime examples. Here

there is language but indirectly expressed—even silence for Merleau-Ponty speaks.

ROLAND BARTHES

Like Merleau-Ponty, the second major figure of French structuralism, Roland Barthes,

was also preparing in 1952 a response to Sartre’s literary theory: Writing Degree Zero

[11.5] was of mould-breaking merit. It offered an entirely different way of understanding

the role and status of writing. Writing was no longer an act of communication, but rather

an articulation that links up both style and language. The writer’s style (whether

romantic, or surrealist or existentialist) is matched with the writer’s langue or language.

This language is not simply idiosyncratic. For Barthes, language partakes of a social

context and experience. Language and style at the intersection of the two marks the locus

of writing (écriture). Hence revolutionary writing or bourgeois writing or romantic

writing occur in terms of a particular language and a determinate style. And such

revolutionary writing can be found equally in the times of Thomas Jefferson, Robespierre

and Brecht. Though the times are radically different, even the language and style are

different, the writing can be called ‘the same’. Although Barthes found that different texts

could be characterized in terms of these repeatable forms of writing, he was also

fascinated with the new writing of Alain Robbe-Grillet. Barthes is credited with having

‘discovered’ Robbe-Grillet, whose style of writing is officially a radical break with the

nineteenth-century novel, but whose writing itself marks the beginning of an

impassionate language where the subject is decentred and the discursive proliferations are

structurally identifiable. Le Voyeur and La Jalousie are excellent examples of a language

stripped of emotion—or at least emotion as described by the typical nineteenth-century

omniscient author. There is still emotion, but it is described through the surfaces and the

ways in which surfaces are affected.

With the 1964 publication of Elements of Semiology [11.7], Barthes at last linked up

his critical practice with the theoretical writings of de Saussure. In this short piece, which

was originally published in Communications, the official journal of the Ecole Pratique

des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Barthes outlines the theory of the sign: the

signifier/signified relation, the langue/parole link, the connection between diachrony and

synchrony, and the opposition between denotation and connotation. But the critical year

was 1966, which saw the publication of his own Criticism and Truth [11.8], Lacan’s

Ecrits, [11.15] and Foucault’s The Order of Things [11.17]. Hence over a decade after

Barthes produced Writing Degree Zero, structuralism finally came of age. Elements of

Semiology set the stage for that crowning moment. In his seminar at the Ecole Pratique

des Hautes Etudes which I attended for the whole year in 1971–2, Barthes focused on

what he called ‘The Last Decade of Semiology’. He considered 1966 as the watershed

year. In the following year, Jean-Luc Godard produced his revolutionary film La

Chinoise (which prefigured the student-worker revolts of 1968) and Derrida published

Speech and Phenomena [11.30], Of Grammatology [11.29], and Writing and Difference

[11.31]. Hence by 1967, a whole new phase had begun—for lack of a more precise term

it was called poststructuralism. Of course, there were still many who were committed to

structuralism for another decade and many of the so-called poststructuralist theories

continued to build upon the languages and lessons of structuralism.

Once the scene was set and the terminology clarified in The Elements of Semiology

[11.7], Barthes himself began to develop his own position further. He rejected those

critical theories that gave special place to the author and authorial presence. And in his

famous essay ‘From Work to Text’ (1971 [11.10]), he outlined very clearly the

distinction between the traditional notion of the ‘work’ and his notion of the ‘text’. The

‘work’ (oeuvre, opera, Werk) results from an act of filiation: an author produces or

creates a work which is then a ‘fragment of substance, occupying a part of the space of

books (in a library for example)’.5 The author requires authority over the meaning of the

work. And the critic seeks to understand the author’s meaning. This hermeneutic concern

pervades work-centred studies. And it was also a dominant feature of the Sartrian theory

as well. Barthes proposes to place the emphasis on the text, which he describes as a

‘methodological field’. He elaborates: ‘The Text can be approached, experienced, in

reaction to the sign. The work closes on a signified’ (p. 158). This means that the text can

be read in terms of the sign system which participates in it, while the work focuses on

what is meant by it. The plurality of the text permits a full and elaborate network of

intertextuality which is closed off by the work. ‘The Text’, he says, ‘is bound to

jouissance, that is to a pleasure without separation’ (p. 164).

Two years later, Barthes published The Pleasure of the Text (1973, [11.11]). For

Barthes, the Text is not an object of desire or even a result of a creative act. Rather the

Text is a site—a locus for a reading, a place in which jouissance occurs. Something

happens in the critical reading of a Text. The Text’s network of signifying dynamic is

brought out. In the Introduction to S/Z (1970), Barthes had already shown how the

distinction between the ‘readerly’ (lisible) and ‘writerly’ (scriptible) text marks the

difference between a text which is simply read through for the pleasure of it and the text

which is read as a methodological field—one in which the codes and sign systems are

elaborated in detail and available for careful decoding. The ‘writerly text is not a thing,’

Barthes writes, ‘we would have a hard time finding it in a bookstore.’6 The ‘writerly is

the novelistic without the novel, poetry without the poem, the essay without the

dissertation, writing without style, pro-duction without product, structuration without

structure’ (p. 5). The writerly occupies only a methodological and theoretical space, it is

not a product like the readerly text.

In this frame, Barthes outlined five different codes which constitute what he calls ‘the

plural text’, and the plural text is the writerly text critically disclosed. The five codes

include: the semic code (the elaboration of the signifier), the hermeneutic code

(disclosure of the enigma), the symbolic code (one element stands for another), the

actantial code (the action code), and the reference code (the cultural indicators marked in

the text). These codes are only possible codes for the reading of a text. Although Barthes

does not dwell upon the alternatives, it is only plausible that alternative sets of codes

function as well as those Barthes invokes.

Barthes was at his most daring when he took up an age-old topic, namely

autobiography, but in a radically new way. Roland Barthes (1975, [11.12]) by Roland

Barthes is certainly a break with the traditional diachronic mode of writing one’s own

life. He organizes his life not according to the succession of years, but according to the

alphabetical arrangement of topics, themes and oppositions that played an important role

in his life. And as to the typical chronology, that can be found in two pages at the back of

the essay. Barthes should not have died so early. He was run over by a milk truck outside

the Collège de France where he had been elected to the Chair of Semiology in 1977. He

was only sixty-five when he died in 1980.

JACQUES LACAN

Jacques Lacan, by contrast, born in 1901 only one year after Hans-Georg Gadamer, lived

to a ripe old age of eighty-one. There is a wonderful cartoon which Barthes includes in

his Roland Barthes of Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, Barthes, Foucault and Michel Leiris all sitting

together in Tahitian skirts. Although reflecting different ages, they all came together

around the structuralist enterprise. Lacan provided the basis for a structural

psychoanalysis. His early 1936 study of the mirror stage was first presented in Marienbad

(later made famous by Robbe-Grillet in the film Last Year at Marienbad). Lacan’s theory

is rather simple: the child at first does not detect any difference between it and its mother.

The sensory world around it is all integrated. It begins to notice a difference between it

and the mother. This becomes clear when it looks into the mirror and sees no longer just

motion or another person, but recognizes an identity between what it sees and itself. It

waves an arm and the image waves its arm, etc. It notices then that the mirror image is

itself. But then the father intercedes: the nom du père/ non du père/non-dupe erre are all

forms of interdiction. The father with his name and his prohibition—after all, he is

somewhat jealous of the close relationship that his child has with his wife—attempts to

break the harmony, introduces a negation, his paternal law, his ‘No’. The father is no

fool. He knows what he wants and he knows what he does not want. By interceding

between the child and the mother, he imposes his authority, his will, his name. Now the

child cannot but recognize difference. The Verneinung is effective. The father imposes

his will and the child learns to affirm its own identity. Thus the mirror stage is the critical

moment at which the child takes on an identity of its own.

The inclusion of the revised version of the ‘Mirror Stage’ in Ecrits (1966 [11.15])

correlates with a number of other essays of major importance. In 1966 there was a

conference held at Johns Hopkins University subsequently entitled The Structuralist

Controversy. While Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato edited the volume, the

leadership of René Girard was crucial. At Stanford, for instance, in the late 1960s one

heard of the Johns Hopkins experiment and those professors of literature committed to an

earlier model of literary study were deeply opposed to the Johns Hopkins scene.

Curiously, René Girard is now Professor of Humanities at that very same Stanford

University after trying out the State University of New York at Buffalo for a brief period.

Lacan was one of the speakers at the 1966 Hopkins conference. Also presenting papers

were Jean Hyppolite and Jacques Derrida. It was an important moment. And Lacan’s

essay was no less important. His paper was entitled ‘The Insistence of the Letter in the

Unconscious’, an essay which also appears in Ecrits. The question is, how does the chain

of signifiers mark off and bar the range of the signified? The signified especially in the

metonymic line is barred from access by the signifier. This exclusion of the signified

leads to a veering off of the signifier from one sign to the next. The signified however

remains unaccessible. The line between the signifier and the signified is strong and

resistant. In such cases in which the signifier has no access to the signified, it must act in

terms of that repression.

In the case of metaphor, there is an overdetermination of signifieds for a particular

signifier. In such a case, the bar is weak and a multiplicity of meanings intrude.

Throughout Lacan’s account, ‘the unconscious is structured like a language’. Where there

is resistance in language, there would be resistance in the unconscious. But for Lacan

whatever there is of an unconscious is read in terms of the play of signifiers. Repression

results when the letter is unable to insist in the signified. Meaning is kept at bay. A

stream of words and utterances follows but the relation to the signified is repressed. With

Lacan, as later with Derrida, the self is decentred, the subject is dispersed throughout

language. The language of the self is the language of the chain of signifiers. The subject

per se remains absent.

MICHEL FOUCAULT

The theme of the absent subject is especially notable in the philosophy of Michel

Foucault, who met an untimely AIDS-related death at the early age of fifty-eight. In his

magnum opus, The Order of Things (Les Mots et les choses) [11.17] also published in

1966—the theme of the absent subject pervades not only his reading of Velázquez but

also his account of the contemporary human sciences. For contemporary

(poststructuralist, or what would now be called ‘postmodern’) thought, there is no centred

origin, no unique place of focus, no present subject as there once was for the modern age.

Foucault’s reading of origins is marked off by his reading of discursive practices. As

he demonstrates in The Order of Things, history does not begin at a certain moment and

then continue—in linear fashion—from then on. Rather, moments of dominance of

certain discursive practices prevail for a time and are then succeeded by a new set of

discursive practices. Where a discursive practice ends, a new one is about to begin.

Origin then will occur where a new discursive practice starts to take place. But where and

when do such new practices begin to take place? They clearly do not occur at a

determined moment in time such as a date or year. Certain discursive practices pertinent

to a particular epistemological space, as Foucault calls it, continue into a new

epistemological space, while others die out.

But what is a discursive practice? For Foucault, a discursive practice is a whole set of

documents produced within a broadly general period of time in which common themes or

ideas occur across that period in a wide variety of disciplines and areas of human

knowledge production. For instance, in the nineteenth century the relations between

biology, economics and philology would seem to be entirely unrelated. However

Foucault has shown that they all consolidate in terms of a relatively singular conceptual

unity, or what Foucault calls an epistemé. For the broad space of the nineteenth century,

Foucault identifies the theme in question with what he calls an ‘anthropology’, that is, the

theory of ‘man’ as defined by the ‘empirico-transcendental doublet’,7 the particular

Kantian idea that empirical (objective) considerations must always be understood in

connection with a transcendental (subjective) set of conditions that permeates the

discursive practices of the nineteenth century. The theme of subjectivity in relation to

objectivity pervades the nineteenth-century understanding of life, labour and language.

Thus the discursive practices of the nineteenth century repeat themselves in a variety of

contexts—all explicitly unrelated to each other. These differences then form an epistemé.

The epistemé of the nineteenth century succeeds the epistemé of the ‘classical age’.

This prior epistemological space is marked by another set of discursive practices. These

include the classification of species, the analysis of wealth and natural grammar. What

one would take to be entirely unrelated concerns are here brought into relation to one

another in that they each exhibit features of the ‘classical age’ epistemé, namely

‘representation’. As Foucault reads the general period of the seventeenth century and first

half of the eighteenth century, the idea of ‘representation’—the projection or postulate of

ideas before the mind—formed the frame for a distinctly ‘classical’ way of thinking. The

relation between this classical epistemé and the nineteenth-century epistemé is much less

significant than the relation between the various practices at each of these respective

time-slices.

The origin of the epistemé is not the beginning of the epistemé. A particular epistemé is

marked by a certain dominance. The place where the epistemé dominates is the place of

its origin. The place of dominance for the empirico-transcendental doublet is the place of

origin within that epistemological framework. Similarly the place of dominance of

representation in the classical age is the place of origin within that epistemological

framework. However, where is this place of origin in each case? Dispersed throughout

the epistemological space, the place of origin occurs wherever there is a discursive

practice that exhibits it. Hence the origin is in many places: reappearing in many

locations throughout the epistemological space itself. In the nineteenth century, one can

find the empirico-transcendental doublet not only in Hegel and Hölderlin but also in

biologists such as Cuvier (whose ‘fixism’ is set off against the backdrop of human

historicity), economists such as Ricardo (for whom history is a vast compensating

mechanism) and philologists such as Schlegel (with his 1808 essay on the language and

philosophy of the Indians), and philologists such as Grimm (most notably in the 1818

Deutsche Grammatik) and Bopp (whose 1816 study of the Sanskrit conjugation system

became an object of study).

Each of these places constitutes itself as an origin, as a locus in which the concept of

‘man’ as a subject-object is brought into discourse production itself. No longer does

language, for instance, operate between words and things resulting in an operation of

representation. And in the nineteenth century, words are objects themselves, objects for

scrutiny and study by a scientific practice that hopes to judge them and their

interrelationships. Origin, then, for Foucault is not a source from which all historical

events follow. Origin is not the beginning from which history begins to unfold. Origin is

not the inception from which development ensues. Origin does not establish the moment

before which nothing else will have occurred. Rather origin springs up in many places

within a broad, general, historical time-frame. Origins occur in various discourses,

scarring them with marks of a common practice that is unaware of its own commonality.

Foucault’s enterprise disperses origin throughout a kind of methodological field (as

Barthes would have called it). And his appeal to the English reader to ignore those ‘tiny

little minds that persist in calling him a structuralist’, indicates that he is already beyond

the mere repetition of structuralist methods. Although his own archaeology of knowledge

could be characterized as largely synchronic, it also relies upon the assessment of periods

or time-slices in order to compare one time-slice with another. What Foucault rejects is

the necessity of a concept of continuity in favour of discontinuity. Structuralists were

already concerned with a discourse of the past. Nietzsche and Mallarmé are invoked as

threshold figures marking the break with the older empirico-transcendental doublet of the

modern age. They mark the beginning of a new mode of thought in which dissemination,

dispersal, metonymy and decentring of the subject are the dominant frames of knowledge

production.

Where Sartre had announced in his 1936 Transcendence of the Ego that the self or ego

could not be located in consciousness but is at best an object of consciousness, Foucault

in 1966 places that claim in a historical context. He situates the end of the age of

modernism with the end of the centred subject, the dominant self, the focal ‘I’. Like

Nietzsche’s madman who ran through the streets proclaiming the ‘death of god’, Sartre

had already proclaimed ‘the end of man’, but in a sense that would not be fully

understood for another thirty years. The linguistic turn in continental philosophy took on

a different shape from that in the analytic tradition. It did not fully take place until the

Saussurian epistemology became the principle according to which language, culture and